Transferring AI Knowledge To Human Understanding

At this week's ML reading group at DeepFlow, we discussed a core question for human–AI systems: how do we distinguish AI that solves tasks from AI that builds human capability? In many settings, the immediate outcome produced by AI agents can look correct while genuine understanding fails to transfer to humans.

This distinction matters most in high-stakes or high-accountability settings—where humans remain responsible for decisions, must justify actions, and need to retain capability as tasks evolve. In those workflows, an AI assistant that only produces correct outputs can still create hidden fragility: dependence on AI without understanding.

That's the tension this paper puts under a microscope: when a model is more capable, does it reliably transfer that capability to the human—or does it simply execute while the human observes?

Why this paper caught our attention

KITE ("When Models Know More Than They Can Explain: Quantifying Knowledge Transfer in Human-AI Collaboration") argues that we're good at benchmarking model performance, but we're much worse at measuring knowledge transfer—whether a human can take what the model explained and then succeed independently.

The authors introduce Knowledge Integration and Transfer Evaluation (KITE) and back it with a human study (118 participants) across challenging coding and competition math problems. The headline finding is uncomfortable (and useful): better models don't reliably make better teachers, and "being a good doer" is not the same as "being a good coach."

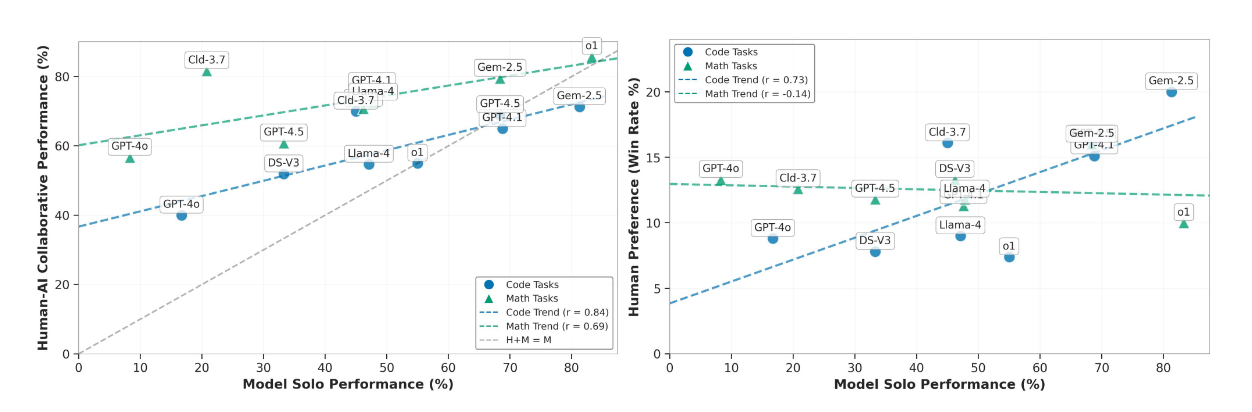

Figure from the paper: The teaching gap. Human+AI performance rises with model strength, but more slowly than model-solo performance (the gap widens as models get stronger), and user preferences don't consistently track which model actually helps people—especially across coding vs. math.

That landed for us because DeepFlow sits exactly in the "human + AI working together" regime—where success isn't just a correct output, but correct output with human understanding, control, and traceability.

What the paper claims

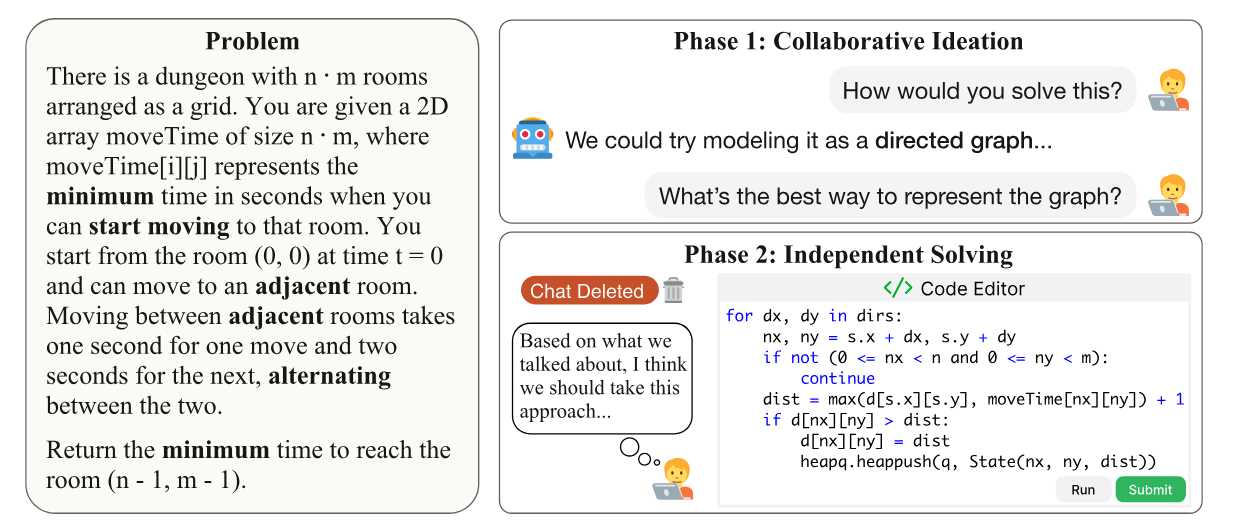

KITE's core move is a two-phase evaluation designed to isolate real learning:

- Phase 1: Collaborative ideation — the human chats with the model to brainstorm a solution, but the setup actively blocks the model from dumping full solutions (no full code / no detailed calculations; flagged responses can be withheld).

- Phase 2: Independent solving — the chat is removed and the human must solve the same problem alone, from scratch, without notes or chat history.

If the human succeeds in Phase 2, that’s evidence the model actually transferred usable problem-solving knowledge—not just an answer.

Figure from the paper: KITE's two-phase evaluation. Users collaborate with the model in an ideation phase, then solve the same problem independently with no access to the chat—so success reflects knowledge transfer, not copying.

Once this scaffold is in place, the results get interesting. The paper compares model solo success vs. human+model success, and finds big mismatches:

- Some highly capable models don't improve human outcomes proportionally, and in some cases collaboration is worse than the model alone.

- Some weaker models can still coach humans to solve problems beyond what that model can solve solo, suggesting teaching is its own capability.

A concrete example the paper highlights: on coding, Gemini-2.5-Pro solves 81.3% solo but human+Gemini solves 71.3% (a −10% drop). Meanwhile Claude-3.7-Sonnet solves 45.0% solo but human+Claude reaches 70.0% (+25%). That's the "models know more than they can explain" phenomenon in numbers. Across models, the paper finds a consistent pattern: collaborative gains grow more slowly than model capability, reinforcing that 'better solver' doesn't automatically mean 'better teacher'.

What we discussed

The discussion focused on a few sharp distinctions:

- "Good doer" vs. "good coach". We liked that the paper treats teaching as its own measurable capability, not a free byproduct of reasoning scale.

- Preference isn't the same as learning. People often prefer high-capability models, but that preference can diverge from which model actually improved their independent success—especially in math, where explanation style matters a lot.

- Theory of mind as the missing ingredient. A recurring hypothesis was that what's being measured is partially "does the model understand what the human is missing?"—i.e., coaching requires a kind of theory-of-mind, not just knowledge.

- Skill calibration and ELO. There was healthy skepticism about using ELO-style ratings for humans/tasks/models at scale, and whether that introduces artifacts—though the study was careful in its setup.

Why it matters for DeepFlow

This paper connects to DeepFlow without needing gymnastics, because our platform is about humans and AI completing real work together, not AI replacing humans.

A few takeaways:

- "Helpfulness" should be measured as retained competence, not vibes. KITE's phase split is a nice template for evaluating whether an assistant is building user capability (can they do it afterward?), not just generating outputs during the session.

- Workflow auditability isn't enough if the human can't re-derive the why. The paper's overreliance failure mode ("trusted the model, skipped planning") is exactly the kind of risk you want to surface and mitigate in human-in-the-loop systems.

- Adaptive delegation needs adaptive explanation. The paper's strongest qualitative lesson is that coaching strategy should shift with user skill: scaffolding helps novices but annoys experts; "one style fits all" fails. That’s a design principle we can apply across human-facing agent behaviors.

Closing reflections

KITE's underlying claim is almost philosophical: a model's intelligence only becomes useful in human-AI collaboration if it can be translated into human understanding.

As models get stronger, it's tempting to assume the collaboration problem is solved. This paper argues the opposite: the gap between what models can do and what they can teach may widen unless we explicitly optimize for knowledge transfer too.

For workflow automation, that’s a big deal. The endgame isn’t "AI that can solve hard problems." It’s AI that can solve hard problems while upgrading the humans who supervise, adapt, and take responsibility for the system.

This post is part of DeepFlow's ML Reading Group series, where we share reflections on the latest AI research and its impact on workflow automation.